Abstract

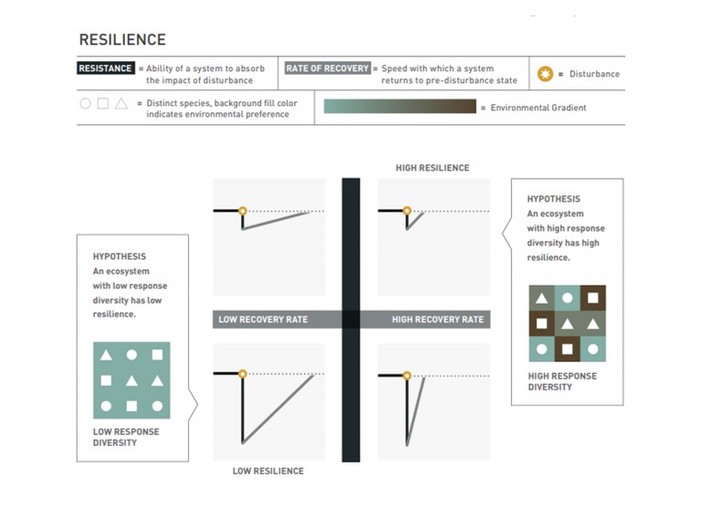

Response diversity, defined as the variable responses of species to environmental change, has been proposed as a key determinant of ecosystem resilience. We test this hypothesis along a tropical dry forest successional chronosequence that provides a gradient of species richness and diversity. The system experienced a strong disturbance from Jova, a category 2 hurricane, in 2011. We assessed the resilience of secondary forests to hurricane disturbance by estimating both the resistance and the rate of recovery of standing biomass, comparing data from several years prior- and post-hurricane. We assessed response diversity from variations in species-level litter production in response to fluctuations in precipitation during the annual wet-dry transition period in five pre-hurricane years. The two resilience components, resistance and recovery rate, were negatively correlated, suggesting these measures of resilience are inversely coupled. We found that historic reductions in basal area through human intervention may not necessarily reduce system resilience to additional disturbances, and may in some cases enhance the capacity to absorb hurricane perturbation. This implies old-growth forests can withstand some level of human intervention and structural change, and persist through a subsequent natural disturbance. In accordance with theory, sites with greater response diversity to climate should also be more resilient to disturbance; however, we found a surprising negative relationship between response diversity and rate of recovery. We speculate this contradictory result may be due to the compounding nature of multiple disturbances interacting with climate change, and suggest our understanding of mechanisms that confer resilience to ecosystems might need reevaluation as anthropogenic pressures related to land-use and climate intensify.